Address

Brynmawr & District Museum,

Carnegie Library,

Market Square,

Brynmawr,

NP23 4AJ.

Tel : 01495 313900

Address

Brynmawr & District Museum,

Carnegie Library,

Market Square,

Brynmawr,

NP23 4AJ.

Tel : 01495 313900

Address

Brynmawr & District Museum,

Carnegie Library,

Market Square,

Brynmawr,

NP23 4AJ.

Tel : 01495 313900

Address

Brynmawr & District Museum,

Carnegie Library,

Market Square,

Brynmawr,

NP23 4AJ.

Tel : 01495 313900

Address

Brynmawr & District Museum,

Carnegie Library,

Market Square,

Brynmawr,

NP23 4AJ.

Tel : 01495 313900

GENERAL INFORMATION

GENERAL INFORMATION

GENERAL INFORMATION

GENERAL INFORMATION

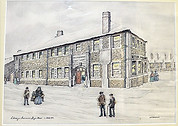

Beaufort Street

I'm a paragraph. Click here to add your own text and edit me. It's easy.

I'm a paragraph. Click here to add your own text and edit me. It's easy.

Brynmawr Museum

& Historical Society

AMGUEDDFA A CYMDEITHAS HANESYDDOL BRYNMAWR

Clydach Ironworks

Clydach Iron Works ( Nr Gilwern at foot of A465 Black Rock Hill)

Established in the late 18th Century near the site of an earlier works and forge, Clydach Ironworks continued operating until 1884. Sited in a beautiful location rich in industrial archaeology, tramroads and pathways, the nearby beech woodlands are some of the oldest in Wales.

Folklore has it that Shakespeare was inspired to write his “Midsummer-Night’s Dream” in a cave nearby, having heard the local legends/story of Pwca (Puck in English)

Smart’s Bridge – Clydach Ironworks ( Near Clydach Ironworks)

Smart’s Bridge was constructed in 1824 to link Clydach Iron Works with sites and routes on the river’s west bank. Arched iron girders cast in mediaeval- Gothic style support a metal-plated roadway provided with hoof grips for draught animals, and grooves for wagon wheels. Restored to almost original condition, the bridge now carries pedestrians both to works and surrounding areas.

(Images of Clydach Ironworks and Smarts Bridge courtesy of Mr Gwyn Jenkins)

Reminiscences of the Old Clydach Iron Works and Neighbourhood - By T. Jordan, Govilon.

(Abergavenny Chronicle, March 11, 1910) - Part 1

The great industry of iron making in South Wales and Monmouthshire is now almost a thing of the past and the famous Iron Kings of the last century, whose names were household words throughout the Principality-the Crawshays of Cyfarthfa, the Guests of Dowlais, and the Baileys of Nantyglo, have long since passed away. But it is still within the memory of many when the hills and valleys in West and North Monmouthshire were at night time illuminated by the great fires of the blast furnaces, rolling mills, and coke yards and when the heavy thud of the monster Nasmyth steam hammer which, it was said, could flatten a ball of iron with ease, or crack a hazelnut without crushing the kernel, resounded on all sides. The cessation of those familiar sights and sounds was looked upon as a great calamity by thousands of working people and so it was, for when the steel-rail trade superseded that of iron, many changes took place, and several important firms declined to go to the enormous expense of changing their plant for the costly one required for the manufacturing of steel rails. Consequently, the discovery of the Bessemer and Siemen's processes doomed the old style of blast and puddling furnaces, and many large works were stopped, never to be re-started, and people traversing these valleys to-day frequently pass huge blackened ruins, the relics of many a bygone industry.

The Clydach ironworks were situated in the parish of Llanelly, in Breconshire, and cosily nestled in a picturesque corner of the valley, under the shadow of the Gilwern Mountain, about five miles from Abergavenny and four miles from Crickhowell. There were four blast furnaces, and the date on one of them, I recollect, was 1797. There had been an older one lower down the valley, at a place called the Sale Yard, which, it was said, was blown by a hand bellows. Part of the ruins was to be seen in my time and a little lower down again was the old charcoal forge. This was said to have been built in 1680 by Captain John Hanbury, one of the Hanbury-Leigh family, of Pontypool, who already had two blast furnaces at Pontypool. Messrs. Frere and Cook, the then proprietors of Clydach works, leased this forge in 1800, and in the course of time Messrs. Powell, solicitors, of Brecon, became partners in the works, and Mr. Frere retired from the concern altogether in 1832. The works were then carried on by the Messrs. Powell until they were closed in 1862. Clydach House, in close proximity to the old forge, is still in existence, and tenanted. It is a fine old mansion, of the Tudor style of architecture, and was the home of the Freres during their connection with the works, and was also the birth-place of Sir Bartle Frere, afterwards Governor of Cape Colony. On a square tablet over the main entrance at the front of the house is the date 1603, which, I presume, would be the date of its erection.

Through the courtesy of the Rector of Llanelly, I was permitted to see the following register,

“Henry Bartle Frere was baptized at the parish church on March 29th, 1815 and died 29th May 1884 and buried at St. Paul's Cathedral."

After the retirement of the Freres, Mr. Lancelot Powell, one of the owners, and manager of the works, took up his residence at Clydach House, and resided there as long as the works continued. To the best of my knowledge, the Powell’s were the sole proprietors of the works, and the family consisted of four brothers, namely, John, Walter, Charles, and Lancelot, and one sister, who married Dr. Prestwood Lucas, a physician of Brecon, and a brother of the late well-known and popular Dr. Lucas of Crickhowell, to whose memory is erected a public fountain in the centre of that town. The vicinity of Clydach House is very wooded and picturesque, with the brook with its quaint old bridge just below and nearby the place known as the Sale Yard. Probably few people now know why it is so called. It is a wide open space, where, at one time, coal was sold to purchasers from the country. I myself have seen the old weighing-machine which had been used for that purpose, as well as for weighing country produce brought in for the use of the works, such as hay, pit wood, &c.

There are still traces of a cluster of old sheds and stables, and at one time the Abergavenny and Merthyr mail coach changed horses there, and there too, stood the little log hut where Molly Dobbs, the Company's post-woman, used to shelter while waiting with the letter-bags for the mail coach as it passed. Methinks I see the sturdy little woman now, as I often saw her, in scarlet cloak and bowler hat, as she handed her charge to the guard when he jumped down from the coach to receive it. This was before the days of Sir Rowland Hill's penny- postage system, and letters then were seldom sent or received by the working people of Clydach.. The Company's bags were opened at the offices every morning, and when letters for other people chanced to be among them they were sent to the Company's shop, where they remained until called for, and many days would frequently elapse before those to whom they were addressed would get them or even know that they were there. Sometimes it was difficult to know for whom a letter was intended, there being so many persons of the same name, and so few known by their right names. The majority of the people on the hills were then best known by nicknames, which were usually selected after a place where they or their forefathers had lived, or worked, or some circumstance connected with their previous history, and prefaced by Twm, Dai or Shoni, Bettws, Shan, or Peggy, and so on.

There were two separate and distinct divisions of' the population, the ironworkers in the valley, and the miners on the “Hill." There was nothing in common between them. They almost looked upon each other as belonging to a different race of people, and not infrequently when they came into contact breaches of the peace were committed which would form the subject of enquiry by the magistrates at Crickhowell, but there were seldom cases of a more serious nature than could be disposed of by a fine of a few shillings; and the late Mr. George Davies, of Court-y- Gollen, who was for many years chairman of the Crickhowell Magistrates, would, when the money was not immediately paid, impatiently shout, "Fork-em-out, fork-em-out," and by that appellation he was often jocularly spoken of by the people.

Mr. Lancelot Powell was a stern man, a true type of the ironmasters of the old school, and one who brooked but little opposition to his will. It was his regular custom every morning to ride up on his well-groomed bay horse to the works and his first halting place would generally be at the offices, whence he would cross to the furnaces, and from there round by the coke yard to the rolling mills, peering keenly into every place as he went along, and any of the workmen who might not be busily employed when he approached knew whether it were best to avoid him or not by the way in which he carried his walking stick whether across his shoulder or twirling it round in his hand. The officials under him were all old servants of the company, well tried and trusted. Most of them had been born and brought up in the place. Mr. Thomas, of Maes-y-Gwartha, for many years the confidential clerk and book-keeper and Mr. Wm. Morgan, the cashier, whose father had been cashier before him, and two of his brothers, John and Thomas, had been furnace-manager at the works in succession. Mr. Robert Ellis from roll-turner became mill manager, and he was succeeded at the roll turning by his son William. Mr. Wm. Davies managed the Old Forge for many years, and Mr. John Reynallt and his brother Charles were at the head of the pattern-makers and carpenters. The former, who had spent all his life at the works, was quite a genius, knowing all the intricacies of the works and the peculiarities of the old-fashioned machinery by which the Inclines were worked. The Griffiths family, too, were old inhabitants, and had been the smiths and boiler-makers of the works from father to son, even to the third and fourth generation.

Then again, there was Mr. Robert Smith the mining engineer, though not a native of the place, he served the Company faithfully for many years. He was a native of Northumberland, and had been recommended to the Company, and engaged by them in 1825. The inhabitants of Clydach, at that time, were greatly prejudiced against strangers, especially English, and Mr. Smith's reception amongst them was by no means of a friendly nature. They called him the “B____y Scotchman," and gave him a good deal of trouble in the discharge of his duties.

There were no policemen in those days only a parish constable here and there, generally old men, and much lawlessness prevailed. When an official in the mining department became unpopular with the workmen, he was in danger of a nocturnal visit from the dreaded “Scotch cattle," as they were called, a band of men with blackened faces, who would drag their victim from his bed, and after doing him grievous bodily harm, would proceed to demolish the furniture. I myself have seen many a cottage clock. its bronzed face disfigured with scars, the work, I was told, of the notorious "Scotch Cattle," a name probably given them on account of their black appearance and the savage brutality which characterised their outrages. They were, I presume, an organization similar to the Mollie Maguires that at one time terrorised some of the mining States of America. The animosity towards Mr. Smith, however, soon passed away, and in the course of time he got to be greatly respected by the workmen. the young people looked up to him as to a father, and called him Y Meister (the master), and many a time did he ride to Crickhowell to speak a good word on behalf of the “Boys” when they had got into trouble, perhaps through a drunken brawl, for drinking bouts frequently ended in a fight, followed by a summons to appear before the magistrates. Mr. Smith retired from the works in 1849, after 24 years' service under the Company.

The following article was found in the Abergavenny Chronicle, 18th March 1910. I am indebted to Thomas Jordan’s great nephew who reminded me of the second part of his great uncle’s reminiscences. Eifion Lloyd Davies 2021

Reminiscences of the Old Clydach Iron Works and Neighbourhood - By T. Jordan, Govilon.

(Abergavenny Chronicle, March 18, 1910) - Part 2

The Clydach mineral property was, originally, part of the tract leased to the Beaufort Iron Works by the Duke of Beaufort, but, with the concurrence of the Duke, the Clydach portion was subsequently subleased to Messrs. Frere, Cook and Kendal. I do not know what the area was, but it was not large, I think. It was a cropping-out corner of the South Wales strata, bordered on one side by the Blaenavon Company's property, and on the other by that of the Nantyglo Company's and, with one exception, that of a shallow balance pit sunk to cut off the long underground haulage in the lower Llamarch level, was reached and worked entirely by levels, across measures, drifts, and slopes, and thereby the workings were drained without having recourse to much expensive pumping. Originally waterwheels were used for the purpose of creating blast for the furnaces and turning the rolls in the mills, but as the number of blast furnaces increased, the old water-wheels gave place to steam engines, which were supplied and erected by the Neath Abbey Company, who were, at that time, I believe, the only steam- engine manufacturers of importance in this part of the country, and a few of their celebrated old Cornish engines are still at work in different places.

The materials (coal, ironstone and limestone) for the use of the ironworks were brought down from the hill by means of inclines, each about three hundred yards long and forming a zigzag line down the mountain side. At the foot of each section of the incline was a level piece of ground forming a landing place, where two men were stationed to pass the trams from one section to the other. The inclines were self- acting, the weight of the full trams going down drawing the empty ones up, and were regulated in their motion by a brake on a wheel over which an endless chain worked and to which the trams were attached. When in motion there were four trams on each side travelling up and down at equal distances apart, one landing at the top when the other reached the bottom, and the men, from continual practice, were quite experts in the work which was carried on with clock- work regularity and precision. By this means about 600 tons of material passed down the inclines each day. According to modem ideas the system was primitive and quaint, but there was great simplicity about it, and, considering the distance and the difficult nature of the ground over which the materials had to be conveyed, it was comparatively expeditious and cheap. The mechanical contrivances of to-day for cheap haulage at collieries were either not known or not resorted to then, and the Clydach Company depended entirely upon horses both over and under-ground; consequently they possessed a large number (probably about two hundred), while for underground work a number of donkeys were employed. There were donkey stables, and it was rather an amusing spectacle to see long strings of those harnessed donkeys, with their boy drivers, going to their work in the morning and returning at night.

The dwellings provided by the Company for the housing of their work people were comparatively few, many of the houses having been built by and belonging to the workmen themselves. The work people were not only allowed but encouraged to build their own dwellings and they were at liberty to select any waste spot they liked to build upon. The people, as a rule, were industrious and provident in their habits, and in addition to sick benefit clubs they -organized money clubs into which they paid monthly instalments of various amounts according to their means, and when the lot fell to them they generally applied the money to some useful purpose, such as buying a horse or a cow or a couple of pigs and a common custom with them was to go to Abergavenny Cheese-fair on the 25th of September, and buy their winter's supply -of good cheese, at a saving price. When a man considered that he was in a position to build a cottage he would select and mark out the place, and in the summer evenings and all spare times, the male members of the family would be engaged in collecting stones, cutting the foundation, and doing what they could towards the building. Sometimes on an idle day at the .works, a couple of friendly hauliers, for a small remuneration, would bring their horses and haul the stones for them. And thus many a snug cottage was built at a comparatively small outlay, and they may be seen at the present time, some of them really pretty little places, with field and garden enclosed by quick or willow fences.

Looking back from our present standpoint, one would think that the lives of the miners at Clydach in those days must have been exceedingly monotonous. There were no public entertainments, and no means of recreation, but such as they made for themselves. Much work and little play was the order of the day. They worked long hours, and during the short winter days very few of them saw daylight from Monday morning until Saturday afternoon. But few holidays came into their calendar, for, with the exception of Sunday, Christmas day was the only one all the year round. Easter, Whitsun, Bank-holidays, and cheap excursions to this and that place were events totally unknown to them; and yet' they were contented with their lot, honest and well conducted, on the whole, and a scandal of any kind in the neighbourhood was very rare. This, I have no doubt, was due, in a great measure, to the influence of the ministers of the different religious denominations and the good effect of the Sunday Schools which were numerous and well attended. Day schools, however, were few and far between, for the children, boys and girls, were sent to work early in life and were brought up very deficient even in elementary education. Superstitious beliefs were fostered among the people to a marvellous degree. They believed implicitly in witchcraft, omens and ghostly apparitions, weird tales of which would frequently be told and eagerly listened to round the village firesides in the evenings—tales of what one or the other had seen or heard, mysterious knockings and death premonitions of various kinds. There were lonely places in the neighbourhood, said to be haunted, places that people dreaded to pass at night time. A notable place was Cwm pwcca (Puck’s dingle), a place charming in the day-time with its beautiful scenery, but notorious on dark nights as the abode of the evil one. One of his Satanic majesty's modes of presenting himself to the benighted wayfarer in that lonely glen was said to be in the shape of a big black dog, which would suddenly confront him with fiendish looking eyes, and then as suddenly disappear in a ball of fire. One of the legends of the place was that of the Bloody well, which is on the side of a lane called Cae-Aberduar lane, and on the stones at the bottom of which were large streaks and spots looked like blood. The story connected therewith was that once upon a time a pedlar Jew put up for the night at a roadside public-house nearby and having imbibed too freely before going to bed, woke in the early morning parched with thirst. Not liking to disturb the inmates, he found his way to the well, and while stooping, in the act of drinking, was killed by a murderous blow on the head, dealt him by the landlord of the house where he had slept, who, having designs upon the Jew's jewel-box, had stealthily followed and murdered him, and the victim's blood upon the stones, like the blood-spots of Macbeth, could not be effaced, and remained an everlasting memorial of the long-ago tragedy enacted in that quiet country lane. Possibly geologists might have a different opinion in regard to those spots upon the stones, but, be that as it may, I myself have seen them: and must admit that they looked very much like spots of blood.

Some little while ago I paid a visit to the place where the old blast-furnaces once stood, and while gazing upon what remained of them, I became absorbed in thoughts of the past, and in imagination could hear the hissing of steam, the rolling of the wheels, and the shouting of men, could see familiar forms and faces flitting about, but returning conscientiousness brought me back to the piles of ruins in front of me, and naught was the same as I had once known it, naught save the old iron bridge on which I stood, and the murmurings of the brook beneath, which seemed to be repeating the words of Tennyson, Men may come, and men may go, but I go on forever."

Bailey’s Tram Road. In the early part of the last century a tramway was made by the Nantyglo Company for the purpose of, conveying the various products of their works to the canal wharves at Govilon. This road was locally known as Bailey’s Tram Road and must have been a difficult and costly undertaking. The length of it would be about five miles and for long distances over Llanelly Hill, the way had to be cut through the solid rock. When the road was completed, a regular system of traffic was adopted, and certain times of the day were arranged for the conveyance of the different kinds of material. About 6 o'clock in the evening each day was the time fixed for the train of rails and bar-iron to pass through Clydach and this traffic was, for many years, handed by Mr. Thomas Parry, of Govilon, with his splendid team of horses. This work was carried out at no little risk, as the road was dangerous, especially on dark nights in the winter- time. The teams consisted of four or five horses, which were led in single file, with a lantern attached to the harness of the leading horse. They travelled at a swinging pace over narrow bridges that spanned the ravines and in many places the road would be within a few feet of the edge of the precipice. The men in charge would walk alongside the train, one carrying a lantern and the others engaged with heavy hammers tightening or slackening the brake-blocks according to the gradient of the road. Men and horses were well accustomed to the work and it was very seldom that any serious accident occurred. Stone walls had been built in some of the most dangerous places between the road and the cliffs, but in course of time they got broken and were seldom or never repaired, and there were no County Councils then to interfere in such matters.

For anyone to have suggested that the day was not far distant when that same route would be traversed by steam locomotives and handsomely equipped passenger coaches, would have been to create a doubt as to his sanity. But in 1862 the present Merthyr, Tredegar and Abergavenny Railway was opened by a local company of which the elder Crawshay Bailey was the chairman and the late Mr. W. F. Batt was the secretary. Soon afterwards the line was transferred to the London & North Western Co.; and travellers over that route are treated to some of the finest mountain scenery in the country while the view of the valley below is of unsurpassed picturesqueness and beauty.

Clydach Valley had been a happy home to its home-loving people for many years, and sad was the breaking up to most of them. As the Vale of St. Taffyd, according to the old song, was to Edward Morgan, of Llangollen, so was the Clydach Valley to them the sweetest of vales where they had lived and loved and brought up their children in respectability. When the old works came to a stand, the blowing out of the furnaces cast a melancholy gloom over the whole district, and all who could went forth and found employment in the adjacent works at Blaenavon, Nantyglo, Blaina, and Ebbw Vale, to which places many of them continued for years to walk over the mountains night and morning, rather than leave the homes to which they were so much attached and to which they affectionately clung as long as they lived. This secluded little valley was the birth-place of several whom, in after life, distinguished themselves among their fellow-men. In addition to Sir Bartle-Frere, already mentioned, there was Dr. Jayne, the present Bishop of Chester, who was born in a village in close proximity to the works. His father, the late Mr. John Jayne, was at that time the well-known proprietor of the Clydach Works and Company's shop. Many others, too, born and brought up in Clydach, have gone forth and occupied prominent positions in different parts of the world.

The entire valley, from the town of Brynmawr to the village of Gilwern, presents to the eye a rare combination of sylvan beauty and rugged grandeur. The river, though generally a sluggish stream, becomes at times a roaring flood, dashing in spray and foam over the shelving rocks and waterfalls, in its downward course to the Usk. The principal waterfall, near the Blackrock village, is well worth travelling many miles to see. A footpath leads from the village down to it, and before the stone bridge which now spans the gulf was built, a narrow plank, with a hand-rail, of rude construction, was the only means of crossing the yawning chasm. The place was originally known as Pwll-y-Cŵn (the pool of dogs), and connecting it, I believe, with the story of a gruesome murder, said to have been committed here some time or other. Nearly the whole course of the river is thickly wooded on either side, and in summer-time glimpses of the stream from the roadway can only be seen here and there, like streaks of silver, far down among the trees. The sides of the ravines through which the small tributaries of the Clydach run are rugged and clothed with rich foliage in summer, where the wild rose and other climbing shrubs grow in wild profusion among a variety of beautiful ferns which cling to the rocky sides of the dells, where the foxes have holes and the birds have nests, and where the stoat and the weasel make their home. Not far above the Black Rock falls are the springs called Ffynon-ish-faen, which means, in Welsh, the well under the rocks. There are several strong springs gushing out from under the banks on either side of the river, which are said to be always of the same temperature and volume all the year round, and to each separate spring is attributed some special medicinal virtue.

The Parish Church is situate on the hill side overlooking the beautiful valley of the Usk, and is about 1 J- miles from the site of the old Clydach works. It is a venerable-looking edifice, consisting of nave and chancel, and a spacious north aisle. Outwardly its grey walls and the ancient yew trees in the church-yard seem to be a thousand' years old, and dates on some of the old tomb-stones refer back to a very remote period. Additional burying ground has more than once been taken in, for the parish is a large one, and many former residents, long since removed to other localities, are being brought there for interment. The large square tower, which is capped with a spire, contains a fine peal of six bells. Until recently there were but five, but the present Rector, the Rev. Geo. Roberts, who has done much towards the improvement of the church and the extension of Church work in the parish, has had another bell added to the peal. The church is again undergoing restoration, the putting of the bells in order being the first instalment.

The six bells in the tower bear certain inscriptions in Latin, the translation of which is as follows:-

1st bell: Holy Elli-May Jesu ever keep this bell sound for thee.

2nd bell: Fear God—Honour the King (date 1626).

3rd bell: Give thanks to God. (1626).

4th bell. Prosperity to all that love good bells; (1715).

5th bell Edward Lewis, Edward Rynald (Churchwardens) date 1715. 6th bell: Gloria Deo—R.J., C.F.C., churchwardens; G.R., rector. C.C. (1908).

The tower in which they hang is of Norman architecture, probably of the early thirteenth century, as the simple round-headed windows suggest. The oldest bell, with its Latin inscription invoking the patron saint Elli, who lived early in the sixth century and founded the Church here long before the Roman Mission landed in Kent, is, on excellent authority, said to have been cast about 1440, by a Bristol founder. The fact that Llan being the Welsh word for church, and Elli the name of the patron saint and founder of the Church seems to explain the source from whence the name of the parish is derived " Llan-Elli," or, as it is now spelt, Llanelly and the Welsh word Clydach, meaning sheltered glade, is a very appropriate one for the valley.

Mr. John Lloyd, of Brecon, published in his Almanack for 1906 a list of the old South Wales iron works, with date of first formation, from authentic papers, from which the following are selected:-

Eastern Division—Sirhowy, date 1790 Tredegar, 1764; Ebbw Vale, 1780; Blaina, 1830; Nantyglo, 1794; Blaenafon, 1784; Beaufort, 1775; Clydach, 1790; Clydach Old Forge, 1680.

Western Division-Dowlais, 1757; Cyfarthfa, 176,; Plymouth, 176,; Penydarren, 1786; Abernant, 1800 Melingriffith, 1800 Aberdare, 1800 Hirwain, 1760 Neath Abbey, 1800.

Thomas Jordan 1910.